By Randy Myers

A little more than two years ago, The Washington Post reported on “the Great American Migration of 2020”—a reference to describe the millions of Americans who were moving in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some were college students leaving campus to return to their parents’ homes, some were middle-aged people heading to their parents’ retirement communities, and some were urbanites escaping to suburbs and rural communities.

While some of those moves became permanent, the big takeaway two years later is that overall migration trends within the U.S. haven’t really changed much.

While there were some pandemic-related spikes in mobility, Riordan Frost, senior research analyst with the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, told participants at the 2022 SVIA Spring Seminar, they appeared to be concentrated among individuals making temporary moves. The U.S. had been experiencing a long-term decline in residential mobility before the pandemic, he said, and the data overall suggested that the most recent mobility trends were just accelerated versions of what had already been happening.

In keeping with those trends, Frost said, most of the migration since the pandemic has been from larger cities to suburbs and smaller metro areas, just as it was before the pandemic. There also been has been continued movement of people away from high-cost coastal metro areas to Sunbelt metro areas, with Florida and Texas particularly popular destinations.

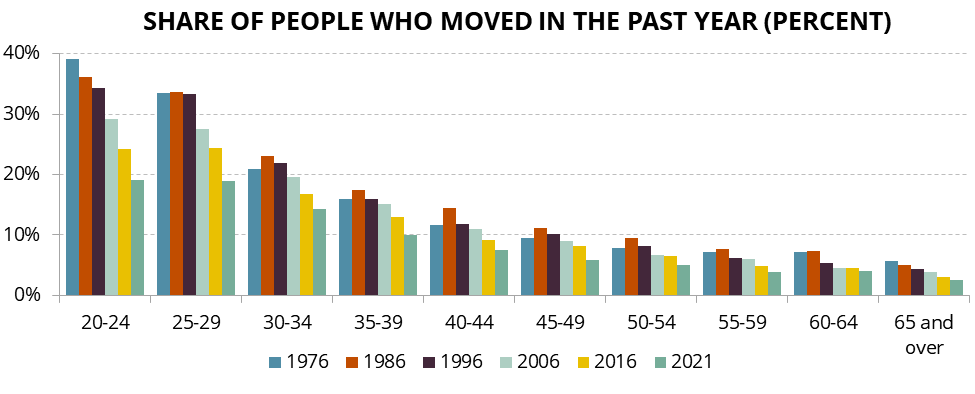

In 1986, Frost said, Census data showed that about 19% of the U.S. population moved. In 2021, by contrast, only about 8% relocated. The declines in mobility rates have been sharpest among young people. In 1976, about 39% of Americans between the ages of 20 and 24 moved. In 2021, the comparable figure was 19%. Declines in the percentage of people moving were found among both renters and homeowners.

More recently, movement by renters continued to decline while movement by homeowners held more steady. In 2021, about 17% of renters were found to have moved within the past year, versus 20% in 2019. The percentage of homeowners moving in those two years held flat at just over 4%.

The most notable upticks in people moving during the pandemic, Frost said, occurred in March 2020, just as the pandemic was gaining traction in the U.S., and was attributable to people making temporary, not permanent, moves. There also were smaller spikes in late 2020 and again in March 2021, but they tended to mirror typical seasonal patterns, and, in any event, mobility activity soon reverted to trend.

Address change data from the U.S. Postal Service show that the number of permanent change-of-address requests rose just 1% in 2020 from the prior year, while the number of temporary requests rose 18%. Permanent requests then fell 4% in 2021, while temporary requests fell 13%. Individuals were more likely to be moving than families. In fact, the percentage of families moving actually fell, according to change-of-address data, in both 2020 and 2021.

The metro areas with the highest net migration gains in 2021 were the Phoenix/Mesa/Chandler region of Arizona (+66,850 people) and the Dallas/Fort Worth/Arlington region of Texas (+54,319). The biggest migration losers were the New York/Newark/Jersey City region in New York and New Jersey (-385,455) and Los Angeles/Long Beach/Anaheim in California (-204,776).

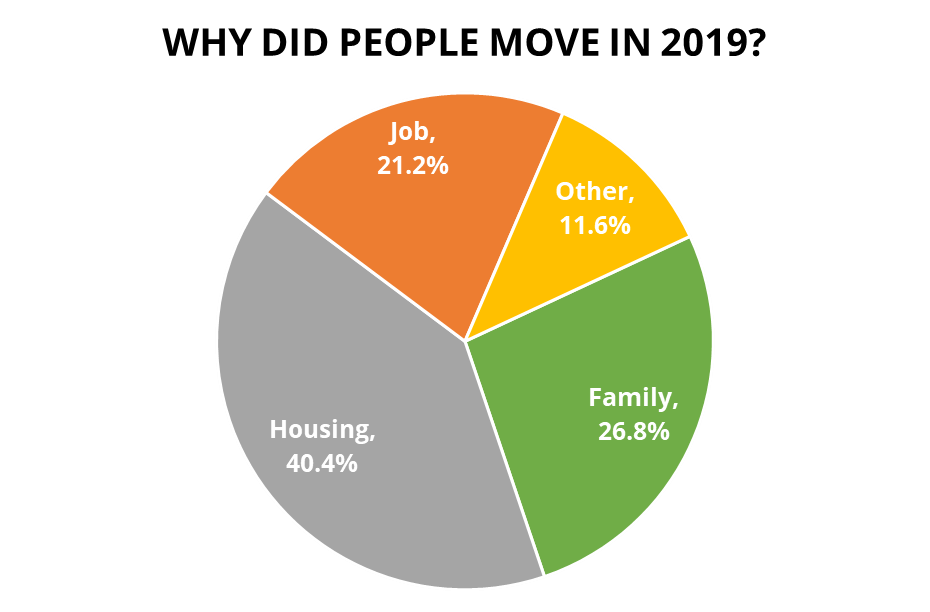

Reasons for moving changed during the pandemic. The number of people moving for job-related reasons fell to 16% in 2021 from 21% in 2019. Conversely, the number moving for housing reasons rose to 46% from 40%, and the number moving for family reasons rose to 29% from 27%.

Looking ahead, Frost said domestic migration trends will become more important to population changes both because immigration rates have been declining since 2017 and because natural population growth—growth attributable to births outpacing deaths—has been declining as well. The latter metric actually turned negative in 2021, with deaths outnumbering births.

Frost observed that the great work-from-home trend, another consequence of the pandemic, may not prove as lasting as some people have been expecting. In May 2020, data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics showed 38% of Americans working from home. By February 2022 that number had fallen to 15%, although that was up slightly from a pandemic low of 12% in December 2021.

The impact of the work-from-home trend on domestic mobility, Frost suggested, may be seen most in the years ahead in the number of people moving from the city where their employer is located into the surrounding suburbs. That would leave them with less distance to travel when they are called back to the office, especially if they adopt a hybrid work arrangement in which they regularly spend part of their time working from home and part of their time at their employer’s place of business.