By Randy Myers

For millions of Americans, saving for retirement is made easier by access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan funded through automatic payroll deductions. For millions more Americans in non-traditional work arrangements—freelancers, sole-proprietors, contract workers and the like—saving for retirement without access to an employer-sponsored plan can be much more challenging.

“Lack of access to a workplace plan is the most significant barrier” to saving for retirement, says John Scott, project director, retirement savings, for the Pew Charitable Trusts. “The current retirement system is clearly not fostering an adequate set of opportunities for non-traditional workers.”

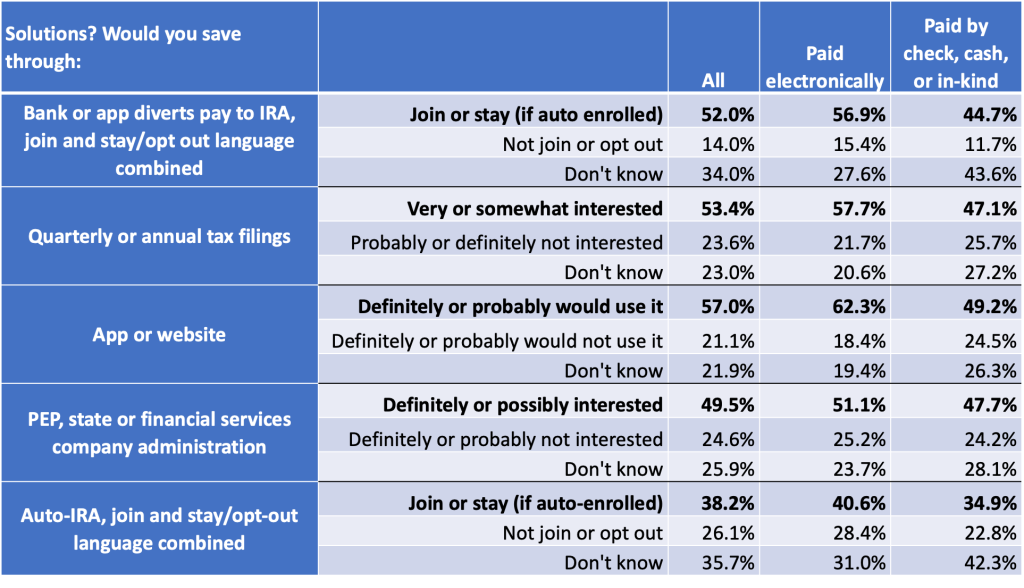

There are, to be sure, options available to them, albeit with limitations. Traditional individual retirement accounts, for example, require that workers take the initiative to set them up and maintain the discipline to make regular contributions. A few select states have recently launched so-called auto-IRA programs for workers at organizations that don’t have workplace plans, but as Scott explained during a presentation at the 2022 SVIA Spring Seminar, those programs are only up and running so far in California, Connecticut, Illinois, and Oregon. Six other states have passed legislation to start such plans, and about ten more are considering similar legislation.

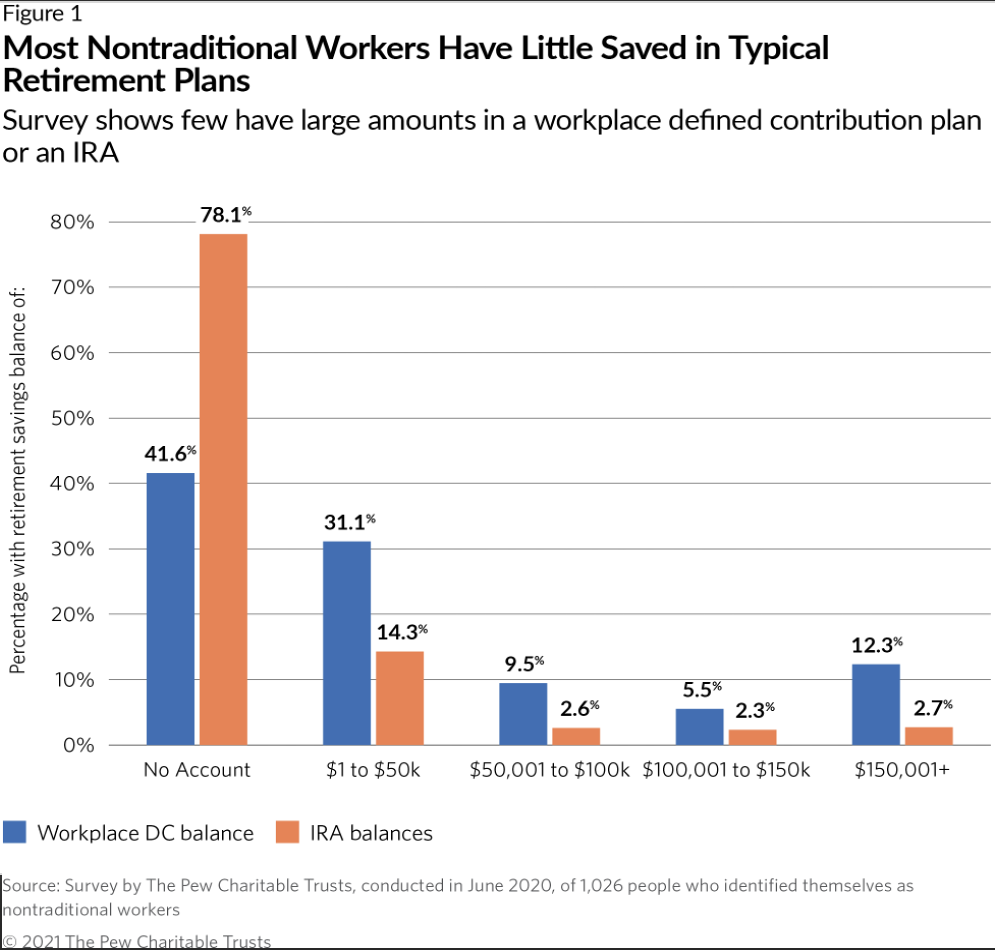

A recent study by the Pew Charitable Trusts showed that most non-traditional workers have little saved in typical retirement plans: 42% have nothing in a workplace plan, and 78% have nothing in an IRA. Among those that do have some retirement savings, only about 27% have more than $50,000 in a workplace plan, and only about 8% have more than $50,000 in an IRA.

There’s no consensus on the number of non-traditional workers in the U.S., with counts varying by how the term is defined. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, with a narrow definition, estimates it at about 4% of the workforce, the General Accountability Office, with a broader definition, puts it at about 40%. In any event, non-traditional workers aren’t the only ones without easy access to a retirement plan, in part because many smaller employers don’t offer one. Overall, Scott said, about 40% of Americans don’t have access to a workplace retirement plan.

This hole in the retirement landscape has implications not only for workers who aren’t saving but also for taxpayers. One study, Scott said, found that in Pennsylvania alone the impact from insufficient savings is $15.7 billion over a 15-year period, counting the cost of increased social assistance for people who run out of money and the tax revenues lost when people can’t spend money in retirement. But the study also found that if all Pennsylvanians increased their retirement savings by just $98 a month the fiscal impact would be erased.

There are some reasons to believe that conditions will improve, although not overnight. Early data from the state auto-IRA plans, which automatically enroll workers without a workplace plan but allow them to opt out if they choose, are proving popular with employers and employees alike, Scott said. As of a few months ago, 61,000 employers in Oregon, Illinois and California had registered for the programs, bringing in more than 460,000 savers who have now amassed more than $440 million in savings. (Connecticut’s plan has only recently started, Scott said, and data from that state wasn’t yet available.)

While the auto-IRA programs implemented to date offer simple and limited menus of investment options, Scott said there may be opportunities in the future to add stable value funds to their investment lineups.

Meanwhile, the SECURE Act of 2019 made it easier for unrelated employers to join together to create pooled employers plans, or PEPs, and also included provisions aimed at expanding the use of multiple employers plans, or MEPs, which are similar but are more commonly used by companies in the same trade or business. While he hasn’t seen a lot of data yet on the impact of the new law, Scott said there has been strong interest among retirement plan providers to organize PEPs and MEPs and offer them to employers.

The availability of auto-IRA programs at the state level doesn’t appear to discourage employers from starting new retirement plans of their own, Scott said. In fact, by heightening awareness of retirement plans, it may be doing just the opposite. In 2020, he said, California and Oregon have some of the highest growth rates of new employer-sponsored plans in the country.

Making it easy to save for retirement will be important to resolving the retirement puzzle for more Americans. Scott noted that simply introducing an automatic enrollment feature in workplace defined contribution plans tends to boost employee participation rates to about 90% from approximately 60%. He also observed that nearly 10% of non-traditional workers say that not understanding how to save for retirement is the primary reason they aren’t saving.

While some have argued that the U.S. should move away from an employer-based retirement system, Scott said he thinks it more likely that the country will end up with a hybrid approach. That approach could include robust employer-sponsored plans and, for those who don’t have access to them, something like the state auto-IRA programs that eventually morph into a national program.