The current economic expansion is already the longest in U.S. history. So it is not particularly surprising that it has been showing occasional signs of winding down. More dramatic is what that might mean.

Speaking at the 2019 SVIA Fall Forum in mid-October, Steven M. Friedman, senior macroeconomist for the global fixed income team at MacKay Shields, an affiliate of New York Life Investments, said the wavering economic outlook has three important implications.

First, he said, the probability of a recession over the next 12 months is now quite high—perhaps in the neighborhood of 40% to 45%.

Second, interest rates may set new all-time lows when the recession finally does arrive. Regardless of when that happens, Friedman explained, the Federal Reserve will need to dig deep into its toolbox to find ways to help the economy recover, including pushing interest rates to ultra-low levels for an extended period. “I would not be at all surprised to see the 10-year (Treasury bond) trading at 50 basis points during the next recession,” he said.

Finally, even after the next recession has passed, it is possible that interest rates won’t rise much. “Yes, rates could make another run at 3% as we come out of that next recession and the next expansion takes hold,” Friedman said. “But something higher than that strikes me as unlikely.” He noted that a variety of structural forces, including an aging population focused less on spending, will contribute to the pressure on rates.

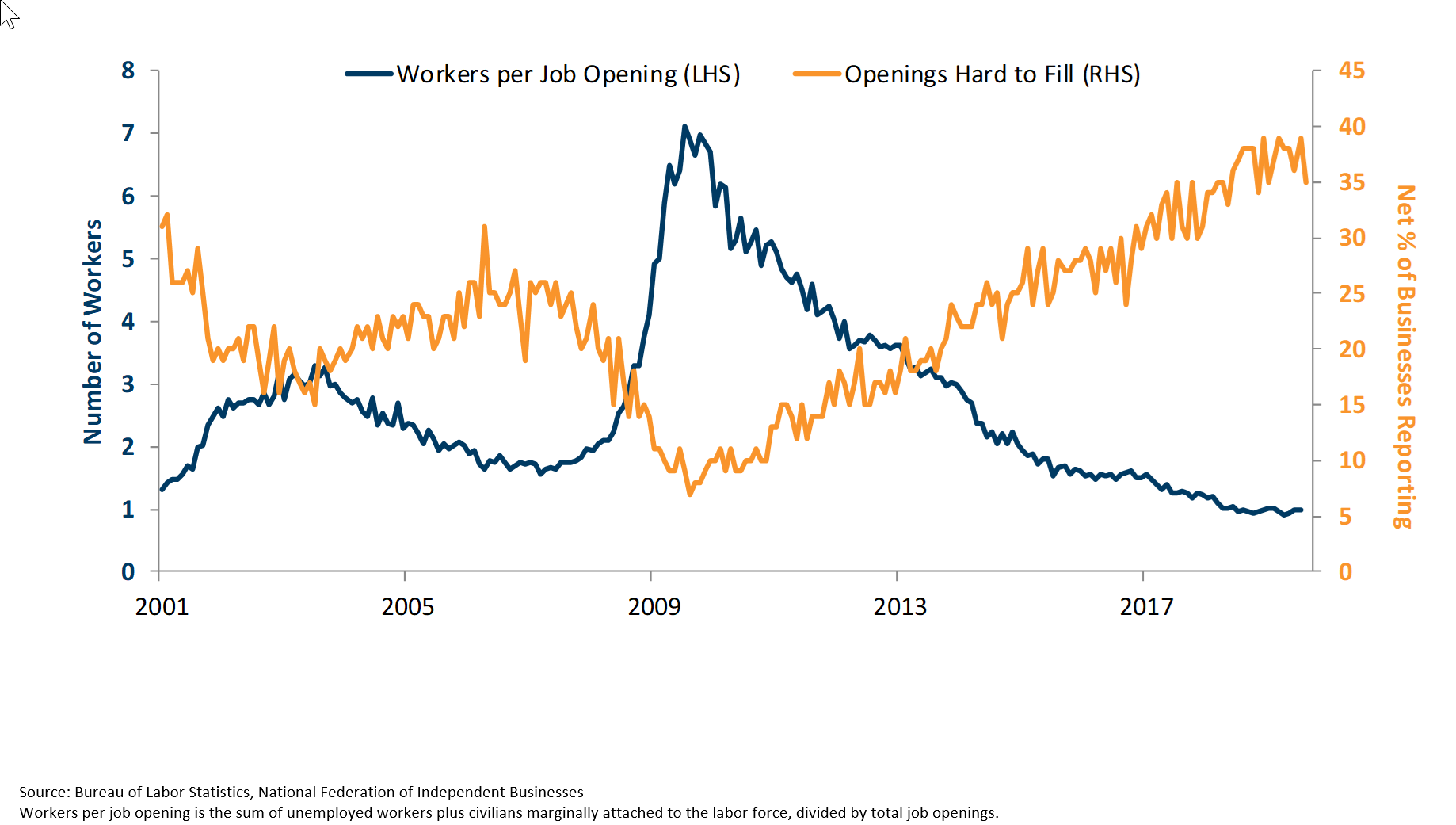

A number of data points suggest the U.S. economy is already under pressure, Friedman said. They include a tight labor market in which the number of workers available to fill job openings is at an all-time low, and declining corporate profit margins at a time when pricing power, thanks to sluggish economic conditions elsewhere around the world, is limited. This leaves corporations vulnerable to financial shocks, especially since businesses are, on average, highly leveraged. U.S. nonfinancial corporate debt equals nearly half the nation’s gross domestic product at the moment, higher than it’s been at any time since at least the 1950s, including immediately prior to the 2000 and 2008 recessions.

Monetary and trade policies are exacerbating the economy’s challenges, Friedman continued. Trade policy uncertainty is contributing to a recession in global manufacturing, he said, with manufacturing activity in the U.S. peaking in late 2018 as the U.S.-China trade war took hold. There’s evidence that this downturn is spilling over into the broader services side of the economy, too, where job growth has recently been slowing. In addition, the number of hours worked by production and non-supervisory personnel has been falling, and consumer confidence, while still generally strong, is deteriorating. Meanwhile, Fed policy moved into restrictive territory last year, and Friedman said the interest rate cuts the Fed has made since then have merely brought U.S. monetary policy back to neutral.

Despite these negatives, Friedman said a recession isn’t inevitable over the next 12 months, particularly if the government does something to remove trade war risks and the Fed becomes more aggressive about easing monetary policy.

On the monetary front, Friedman said the Fed may need to take extraordinary measures to combat the next recession beyond lowering interest rates, since its hands are somewhat tied there. The neutral level for the federal funds rate—the rate at which banks borrow from each other overnight, and for which the Fed sets the target—is now lower than it was a couple of decades ago—perhaps below 1% in real terms, Friedman said. That doesn’t leave much room for the Fed to take rates lower to stimulate the economy.

That means the Fed may need to look to the example of central banks in Japan and the euro area. The European Central Bank has committed to keeping interest rates low in the euro area until inflation is back to the bank’s target. The Bank of Japan has commitment to doing quantitative easing until inflation there exceeds its target, and also has set a cap for yields on 10-year government bonds.

“I think the Fed is going to do something similar in the next recession,” Friedman said. “Even yield curve control focused on shorter-dated maturities is a possibility.”

Friedman also said it would be helpful if the Fed and policymakers in Washington coordinate more closely during the next recession. In the meantime, he said, policymakers in Washington should plan now for how they might provide more fiscal stimulus to the economy should it be necessary.

“But it has to be smart fiscal policy,” he elaborated. “It can’t just be (that) you’re in a recession, so you cut taxes or hand out money. That just supports growth in the short term. You need a fiscal policy that can do something about low-trend growth. So you need investment in education. You need investment in infrastructure. And without getting too much into politics, you probably need an immigration policy that is welcoming of workers from abroad.”

Those may be tall orders in the current political climate, but Friedman suggests they could help support long-term growth.