After more than four decades as a Democratic pollster, Peter Hart knows there’s too much time between now and November 2020 to predict who the next president of the United States will be. But the founder of Peter D. Hart Research Associates has strong ideas about what will shape the outcome of the next presidential election. High on his list: the economy, the impeachment inquiry around President Trump as he seeks a second term, and the type of candidate fielded by the Democrats.

There are, he concedes, some wild cards. All parties readily agree that Trump is not a traditional candidate. In fact, Hart says, Trump will benefit from the public’s perception of him as a Washington outsider even after three years in office, given that 48% of the American public still believes “we need to keep shaking things up and make major changes in the way government operates.” Hart also points out that the nation remains extraordinarily polarized politically, with the Republican base continuing to strongly support Trump while Democrats almost universally oppose him. That sharp divide has driven 69% of Americans to say they already have a high interest in the 2020 election even though it’s still a year away. The comparable figure in October 2016, just one month before the last presidential election, was only minimally higher at 72%.

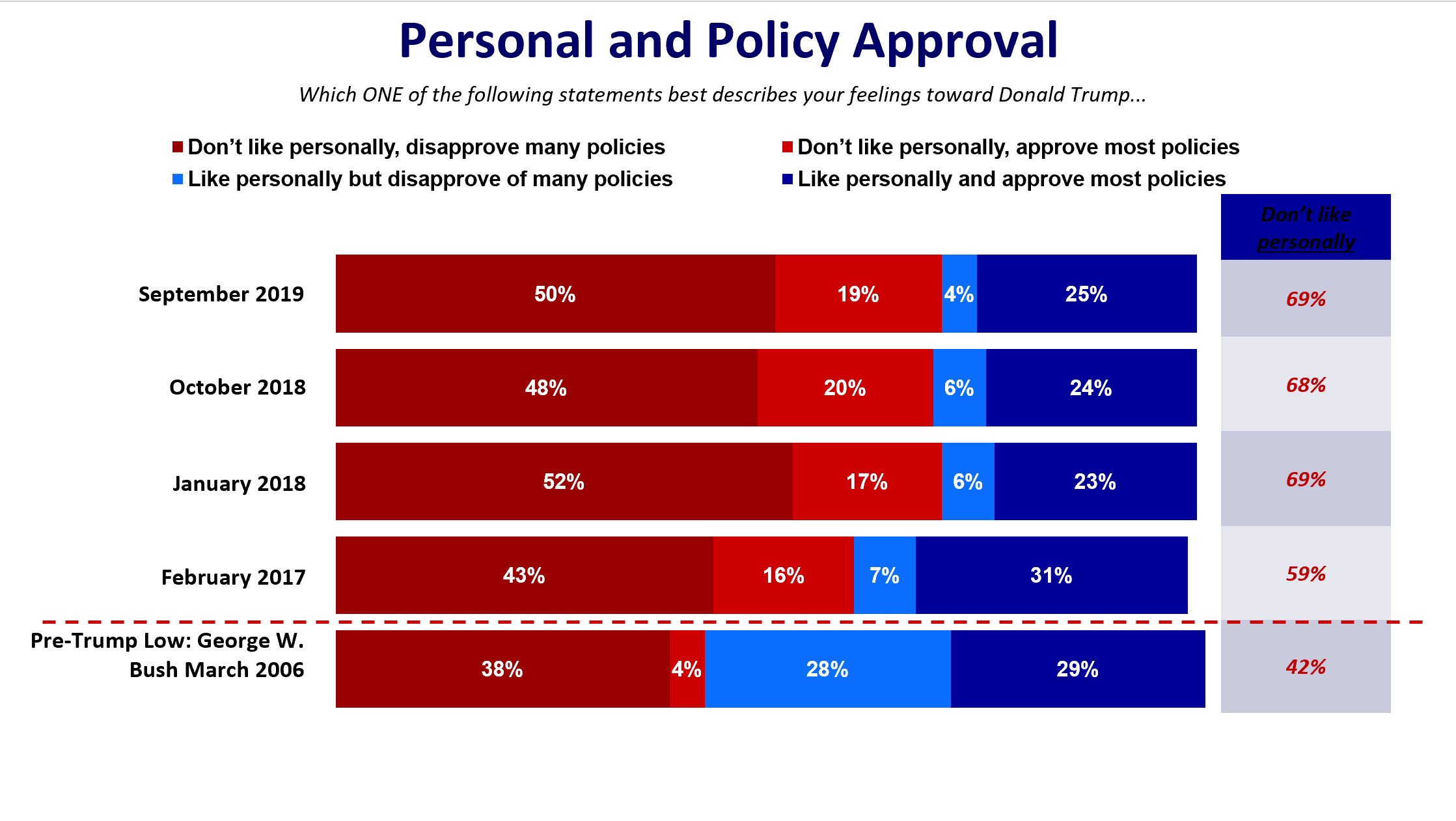

Speaking at the 2019 SVIA Fall Forum in Washington on October 15, Hart noted that Trump goes into the 2020 race with the economic wind at his back—51% of Americans approve of the job he’s doing with the economy. But, Hart said, the president also faces an array of challenges. For instance, half of Americans say they don’t like Trump personally and don’t like his policies either. By contrast, only 25% say they like both the man and his policies.

Even more worrisome for Trump, Hart said, is that 62% of Americans believe the country is headed in the wrong direction. Hart’s firm has been asking voters whether the country is on or off track since 1971, and Hart said it’s proven to be a powerful predictor—“the equivalent of an EKG of American politics.” Since the late 1980s, he noted, the incumbent party has lost the White House when a majority of the electorate felt the country was headed in the wrong direction—at the end of George H.W. Bush’s first term, at the end of George W. Bush’s second term, and at the end of Barack Obama’s second term.

The impeachment inquiry currently underway in the House of Representatives also looks worrisome for Trump, Hart said, in large part because so many Americans—43% in one recent poll—already say Congress should remove Trump from office. By comparison, that number was much lower near the start of the last two impeachment inquiries—19% in June 1973, six months after two aides to President Nixon were convicted of crimes relating to the Watergate break-in, and 24% in October 1998, as the House was approving an impeachment inquiry against President Clinton. By July 1974, one month before Nixon resigned, the figure had jumped to 46%, and by January 18, 1999, less than a month before the Senate acquitted Clinton, it had risen to 32%. The takeaway, Hart said, is that the public’s support of impeachment can grow substantially over time.

“If you start at 43%, you’ve got big problems,” he continued. “It’s not that the American public can’t turn and change and say the evidence doesn’t show anything. But you just don’t want to start at 43%; it doesn’t take very much to work up from there.” An October NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll looked even worse for Trump, Hart said, with 58% of respondents in support of an impeachment inquiry by Congress, and 49% saying the House should vote to remove him from office.

For all this, Democrats hoping to unseat the president at the ballot box face challenges of their own, Hart noted. For starters, the U.S. economy is continuing to grow, and a strong economy traditionally helps the incumbent in a presidential election. Meanwhile, a majority of Democratic primary voters are backing a range of progressive policies that only a minority of general election voters support, including halting fracking, canceling student loan debt, providing Medicare coverage for all, and providing government healthcare for undocumented immigrants. Nominating a progressive candidate who advocates for those positions could turn off independents and moderate Republicans who could be crucial to helping a Democrat win the White House.

“The one thing Donald Trump must have is an opponent that becomes unacceptable to the majority of the electorate,” Hart stressed. “The point here is there isn’t a natural (alternative in the Democratic Party). There isn’t somebody you look at and say, ‘Well, they corralled the American public.’ So in the primary process either somebody is going to have to be able to step up and move forward, or the Democrats are going to be in the same position as the Republicans.”

Regardless of who the Democrats nominate, Hart said that with so many Americans unhappy with the country’s direction, and half opposed to both Trump and his policies, the only way for Trump to win reelection may be to conduct a negative campaign and “make the opponent worse” than him.

While the outlook for the presidential election remains cloudy, Hart said the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary early next year will go a long way toward sorting out who the real contenders for the Democratic nomination will be. And even before then, the November 2019 election for general assembly seats in Virginia could prove an early indicator of how the 2020 presidential election will play out. Democrats have made big gains in Virginia in recent years, but Republicans still control its general assembly by a thin margin. “I honestly believe that if you see a major move there, it tells you something about the mood and where we are starting this election,” Hart said.